Even a king has to negotiate, Aretae says. Doesn’t that mean that every government is a coalition, with all the nasty effects that entails?

Certainly a monarch will make deals — with customers and suppliers. Nike threatens to move its factory unless it gets a better tax rate? That sounds like it might be a good deal. Reducing tax is, for the monarch, giving away cash out of his own pocket, but if he’s getting value for money, why not? That doesn’t mean that Nike are suddenly insiders in the coalition, or threats to royal power.

Ah, but now the CEO of Pineapple Computer Co is on the phone. He has a bit of a problem with a foreign journalist who has been investigating worker suicides in the Pineapple factory. Has Your Majesty heard that Queen Tamsin of Lower Congo has just created a duty-free enterprise zone for technology industries? Of course, that’s of no real interest to him, given Pineapple’s close relationship with Your Majesty. It’s not as if he could trust Queen Tamsin to make an awkward media problem just go away…

Yes indeed, it’s only natural that Your Majesty wouldn’t want to interfere in details like that. It’s a matter for the provincial judge, after all. Although, he is getting a bit old… these personnel matters are such a drag. For instance, Pineapple’s local legal affairs director is looking for a career change, says he wants to do “public service” of some kind. I bet he’d love to become a judge here. He would handle investigations of industrial accidents, to either workers or visiting journalists, with all the appropriate diligence.

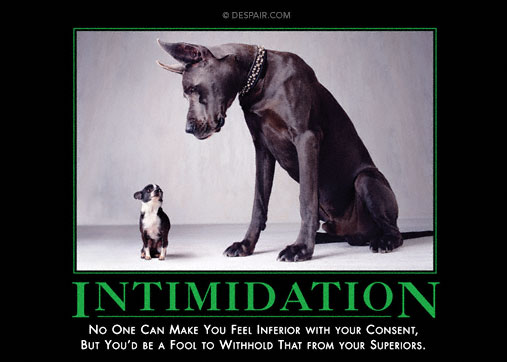

Now is there a coalition?

It looks like the king is starting to give away power, rather than just discounts. In principle, he could dismiss the company’s chosen judge at any time, but he’d be starting a fight that he started out trying to avoid. And the longer the company’s foothold in power lasts, the more it will come to seem like an established right.

On top of that, he’s opening himself to blackmail; he may not have voters to pander to, but there’s a level of bad publicity that can be seriously damaging to his interests.

It is conceivable that such compromises could accumulate to the point where the king is just one player among several jostling for control. Such things have happened historically, though usually from a point where the monarch is much less than absolute to begin with (as most historical monarchs were).

It’s also obviously the case that a state needs some minimum level of power to be able to resist outside influences. A backward, penniless third world country simply cannot be independent, under a monarchy or under any other structure of government.

I think it’s the case, though, that a very large concentration of power is much more stable than a more even division. It is when your power is weak that you find you need to give away more of it, and outside influences can play one element of the coalition against another; on the other hand, for a strong ruler, small delegations of authority really can be taken back if the delegate shows signs of having ideas beyond his station*. Historical monarchs, though mainly less powerful than I am hoping future monarchs will be, were jealous of their power as a matter of principle, and reluctant to tolerate extensions of rivals’ scope.

That retention of power does not come for free, of course. As I mentioned a few weeks ago, rapid economic and technological change is disruptive to any political order. Any political system is likely to try to restrain change that is threatening to those currently in power. Otherwise, it will swing power in a somewhat random direction.

I would prefer to have unrestrained technological change, but I don’t think it’s on offer. Where it has been allowed in the past, I think that has been where an interest group has come to power on the back of a technological change, and has had to support the principle at least temporarily to justify their own position, or where the group in power has simply not recognised the threat that technology holds to them.

In this as in other matters, the more secure the regime, the more confident it will be of being able to benefit from technology while riding the shocks.

And once again, note that the chief value of our current arrangements come, not directly from the division of powers, or from the accountability of elections, but from the security that the regime as a whole has, due to its universally respected right to be in charge. The ruling establishment, large and diffuse as it is, has nevertheless imposed gradually a whole lot of changes that would have been unthinkable when my parents were the age I am now. If they are restrained at all, it is only in the pace of what they can do, not in its limits.

Aretae could argue that the very size of the establishment means that more lunatic ideas are ruled out by a process of averaging. On the other hand, that is counteracted by the effect of groupthink, and the sincere belief among members of the establishment that they really are the only people who matter. Megalomania is an occupational hazard of rulers, but a lone king is likely to notice when he is in a small minority — our rulers seem genuinely oblivious.

* It’s not relevant to the question, but I’m actually curious about ideas like that “beyond his station”; in Britain, at least, the moral principles that go with aristocracy are old-fashioned, slightly comical to most, and violently detested by some, but they are still very familiar. It was essential to the old system that only the right sort of people could hold influential positions. It was never a closed caste, but you had to at least show that you respected the hierarchy and were committed to it before you could be allowed into it. It is very important to the stability of the system that actual power stays where it belongs; outsiders can live and prosper, but they must stay outsiders. The worst case is when the proper authorities are secretly under the control of outsiders, as in G. K. Chesterton’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much”.