Cars as transport

It’s a long time since I wrote about cars.

For most of the history of this blog, I didn’t drive a car. I studied or worked in London for twenty-five years, and London has very comprehensive public transport and not much parking space. I also love walking.

So, when it comes to transport, I am by no means a car fanatic. It’s true that I wrote in 2013 that the advantages of rail travel would come to an end, but that is based on future technological changes that have yet to occur. For the time being, there is still much to be said for rail, and other alternatives to cars have a longer future. So to those who see car usage as a problem to be reduced, I am not really hostile

The thing is that arguments about cars as transport are only addressing part of the story. There is another significant aspect to cars in our society today — a practical aspect, not any psychological mumbo-jumbo about fetishism.

Virtual nations

Particularly in libertarian circles, there is an idea that there could be “Virtual Nations”. Instead of belonging to a country filled with the horrible people who just happen to live near you, you can form a virtual nation along with people like you. You spend all day on the internet anyway, so these people are your real neighbours. You can pay taxes to your virtual nation, vote for its government, invest in online common infrastructure, and make up a really cool flag. It’s been a while since I came across any of these manifestos, but these days blockchains would definitely be involved.

Obviously this is really stupid1 even without blockchains. As Russia has just reminded us, nation states are fundamentally about force. If you don’t have a border you can defend, you ain’t a country. Your relationship with your horrible neighbours is the problem, and a nation-state is the solution. Additional features of nation-states, such as flags, football teams and welfare states, are secondary.

Your country is tied to your geography. It is, however, possible to make a mini-country within a country. Devolution, federalism, subsidiarity are formal mechanisms, but there is an informal kind of partial seccession that goes down to the level of gated communities, office parks, and so on. These are not quite virtual nations, but, being based on physical separation, it is something real.

In the last few decades in our societies it has become something highly prized by the rich. It is a definite social shift, triggered by the rhetoric of equality and enabled by technology, that the rich have much less contact with the rest of the population than ever before. The rich no longer have servants in significant numbers, whereas as I’ve mentioned before, it used to be that 25% of the population worked as servants. Where the rich still rely on service work by humans, huge effort has gone into depersonalising the relationship. This allows us to pretend that we are all equal, that we all do our different jobs. I might be working for you right now, but then you might be working for me later on – there is no relationship of superior to inferior. There is some truth to this, but only some. There are plenty of people who have the practical status of masters over people with the practical status of servants, but they are all theoretically equal and we maintain that illusion by minimising any personal contact that would either dispel it or break the economic relationship.

More importantly, we now live in a society of pervasive violent crime. I have written much about this over the years, because it is controversial, but I think it is possibly the most important single fact about the modern world. My summary is here, and this whole piece is a restatement and elaboration of that one. There are vastly more people in our societies today whose behaviour is dangerously criminal than there were when our civilisation was at its peak, which I would put very vaguely as 1800-1939. To the extent that this isn’t overwhelmingly obvious through crime statistics, it is because of the phenomenon I describe here — people are protecting themselves from crime by physically separating themselves from the criminals.

The polity of drivers

And this is why discussing car usage solely in terms of transport is so pointless. Virtual Nations are in general stupid, but “people with cars” actually do effectively make a virtual nation. To be a citizen of Great Britain you don’t need much paperwork, but to be a citizen of the nation of car drivers you have to register yourself with the bureaucracy and keep your information with them up to date. Because you own an expensive piece of equipment that the state knows all about, you have something that they can easily take from you as a punishment. In fact, they can take it even without going through the endless palaver of a court case. In the last few years, you are even required to constantly display your identification which can be recognised and logged by cameras and computers, so the state for much of the time knows exactly where you are.

I used to find this outrageous, and it is still not my preferred way for a government to govern a country effectively. But it is a way to govern a country, and, unlike Great Britain, the country of British car-drivers is actually governed.

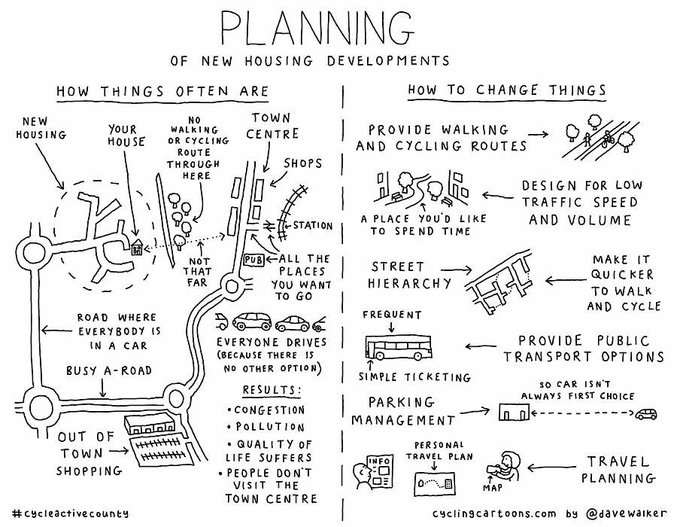

But what about the objection to virtual nations? The virtual nation of car-drivers is not a true province, like Wales or Texas, but it is physically separated from the rest of the nation. That is the point of suburbia, of the windy housing estates full of dead ends, with no amenities and no through roads. If you drive a car, you can quite easily have a home that is not accessible to anyone without a car. When you do have to venture among the savages, you do so in a metal box with a lockable door.

The above image is taken from a 2020 twitter thread by @JonnyAnstead. It is an excellently written thread, and makes perfect sense if you ignore the question of crime. In the absence of that key item, he is left to think that all these car-centric features are either a mistake, or some weird conspiracy of car manufacturers or road builders. In reality there is massive demand for housing in this form, because it permits the buyers to immigrate into the virtual nation of car drivers. As I tweeted at the time, “The cars vs people question is just another aspect of the central issue: the biggest value of a car is that it enables you to stay away from the people who don’t have cars.”

The alternative to cars

There are reasonable alternatives to cars for transport (in a lot of cases, anyway), but we need an alternative to cars as a safe virtual nation to live in.

If you want a society that is not centred on the car, for everyone who can afford one, then put the criminals in prison. That’s it, end of tweet.

OK, this isn’t a tweet I suppose. How exactly to put the criminals in prison is a somewhat bigger question, but it has to be done. I have written about it many times, but, aside from the post linked already, there is this one, where I mention how it should be, and this one, where I describe how it is today. The police and court system is just too inefficient to function. Issues like antiracism, sentimentality, checklist culture have all have their impact, but I don’t think there is any one cause. It has just got steadily less efficient because it was allowed to, and it probably has to be scrapped and rebuilt from scratch. “Tough on crime” politics is totally useless, because no politician inside the system can actually admit how bad things are, so they always rely on showy but incremental items that have negligible practical effect.

Update: Did a little editing that I should have done before posting. Also, the discussions of town planning that this post arose from were referring to Britain; I didn’t generalise to the US. But Candide tweeted: Uhm. What do you think white flight was if not mass emigration to the nation of America-with-cars? — which seems pretty persuasive to me.